Niagara-on-the-Lake’s municipal heritage committee continues to work with a developer who plans to build a 129-suite hotel at the site of the former Parliament Oak School. With the building slated for demolition, their recent meeting was the second one to discuss how pieces related to the property’s history will be preserved and incorporated into the proposed project and had some new recommendations since the last time the project and a notice of intent to demolish the building were discussed.

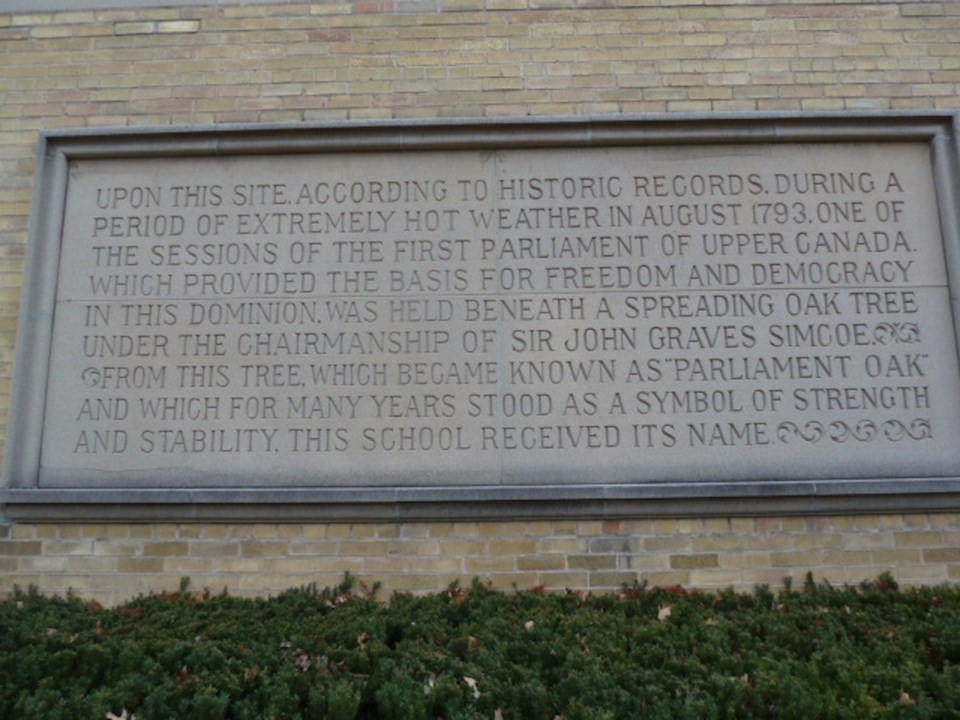

On their list for the second time was the well-known text panel on the front of the former school, familiar to residents as an integral part of the school’s history, that describes the site as where one of the first sessions of Upper Canada Parliament occurred in August 1783, for which the property is much celebrated.

But researchers from Stantec, the firm behind the commemoration plan, argued that the information that is part of the fabric of the town’s history is wrong.

And it seems nobody can prove it isn’t.

In August, Lashia Jones, a heritage consultant who is part of the team behind the proposal, said “dates and times don’t add up,” and that according to research, John Graves Simcoe, who is said to have chaired the meeting, was not in the area at that time.

The commemoration plan included in last month’s heritage committee meeting agenda says that on Sept. 17, 1792, Graves Simcoe held the first session of parliament for the new colony of Upper Canada, and that the “exact location” of the first session of parliament is unknown.

Both the town and the NOTL Museum responded to The Local’s questions of the authenticity of the plaque’s long-accepted description of the town’s history.

Sarah Kaufman, CEO of the museum, explains: “The town reached out to us, in our role of town historian, for clarification on this historical narrative a while back. I discussed it with a few of our historians/researchers in the community. It was decided that there is no conclusive evidence that Parliament Oak School is the location of a Parliament meeting.”

However, she adds, it has been used as a “marker location” to talk about the history of the first Parliament, since there is no other reference to the location that she is aware of.

Town spokesperson Marah Minor says “Even though what has been inscribed on the panel for many years has been a part of local history and the town’s identity, it appears the local government isn’t contesting the opinion in the commemoration plan, from Stantec, that it may contain historical inaccuracies.”

They concluded that “it is unlikely that any parliamentary proceeding took place under an oak tree at present-day 325 King Street in August 1793,” as was indicated on the text panel, said Minor. “Other sources suggest that the year may have been 1792. The date has never been corroborated through historical sources.”

“The local lore that a Parliamentary proceeding took place on the site has long roots” in town, and municipal heritage staff have recommended that the event be recognized through any redevelopment on the site, added Minor.

“Further, it is suggested that interpretive plaques could be incorporated alongside the textual panel that corrects any inaccurate information.”

Due to these findings, the developer wasn’t planning to use the panel in its commemoration.

But town staff are recommending an amendment to the developer’s plans — that this panel is retained and placed fronting King Street.

Town heritage planner Denise Horne also noted to the committee that receiving the report related to plans is “not an approval” and that the committee’s decision still needs to go back to council.

Sara Premi, legal counsel for the developer, Two Sisters Resorts, said it is possible that the text panel could be part of the commemoration plan, even though it was their initial opinion that it shouldn’t be due to alleged historical inaccuracies.

“We are considering that, and I think that’s likely to happen,” she said.

Its location proposed by staff, fronting King Street and not Regent Street, is something that raises “some concerns,” but the developer’s team will “look at that” as well, said Premi, noting that the project’s traffic engineer and architect will need to weigh in on this possibility.

The bas-relief panels, as well as a stone-incised oak tree panel, the Parliament Oak School sign, bricks from the former school, a sculpture related to the Underground Railroad, are other components the developer says it will incorporate into the plans.

In a second report on the meeting’s agenda, the committee also reviewed a heritage impact assessment of the site, which touches on the design value, its historical and associative value related to the story about Sir John Graves Simcoe, and its “direct association” with the public education system in Niagara-on-the-Lake, said Horne’s presentation.

Its contextual value, that the site is historically linked to the development and growth of the town, functioning as an educational institution for more than 60 years, is also important, said Horne.

It was also recommended that the town enter into a temporary heritage easement agreement, which would apply to the preservation of heritage attributes for “any new development” on the property, she said, and that it would apply to potential future owners of the property.

Coun. Gary Burroughs, council’s representative on the committee, asked who will be responsible for costs related to removal and storage.

“It will all be on the property owners,” replied Premi, the developer’s legal counsel, adding it is preferred that items be stored safely off site.

Where they will be kept is a matter “we will have to discuss,” said Premi, noting that the developer is in conversation with the town about a municipal facility being used.

Heritage committee member Amanda Demers asked about “more delicate” items, such as those contained in a 1948 time capsule.

“Once you take them out and expose them to modern air, things can degrade rather quickly,” she said.

Jones, the developer’s heritage consultant, said it is expected this would be handled by someone with museum or archival experience.

Alex Topps, the museum’s representative on the committee, said he’s already started that conversation and that the museum is interested — even though there may be issues with available storage space.

“Putting that aside, we’d be happy to have them,” said Topps.

Council first received the notice of intent to demolish the school in February, but asked in April for more information, which was submitted by the developer in early August.

The Ontario Heritage Act requires a municipality to issue a demolition permit 60 days after the notice of intention to demolish a building, and additional plans and information have been submitted, which would be Oct. 1.